Thirty percent of American households where people have lost income because of the virus have missed meals or relied on food handouts in recent weeks, according to a Kaiser Family Foundation poll.

Many people who are new to worrying about getting food had low incomes at the start. Approximately a quarter of people making less than $40,000 year said the virus has pushed them to skip meals or seek free food, the poll found.

But the surprise to many food bank managers — and to their new clients — is the number of people one step up the income ladder, in the $40,000 to $90,000 range, who are short on food. About 12 percent of Americans in that income bracket said they have missed or cut the size of meals in recent weeks.

“We have a group of people who are suddenly struggling to get food,” Santa Fe Mayor Alan Webber said. “They’re people who are really unused to asking for help, people who thought they had a pretty good handle on life.”

Read full article here / text above & below by Marc Fisher/The Washington Post

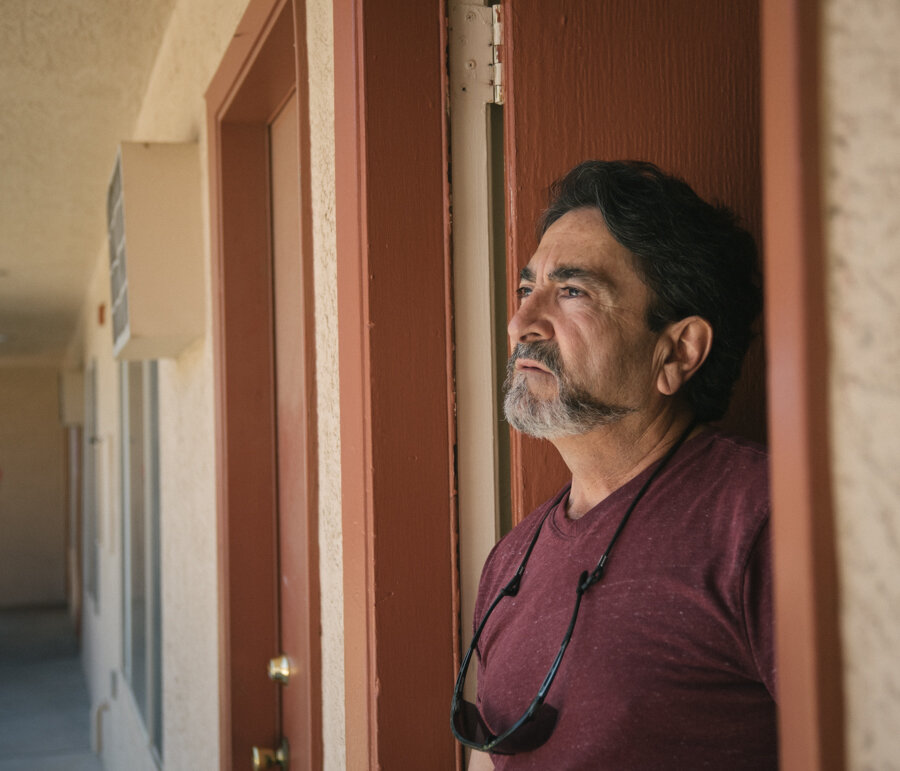

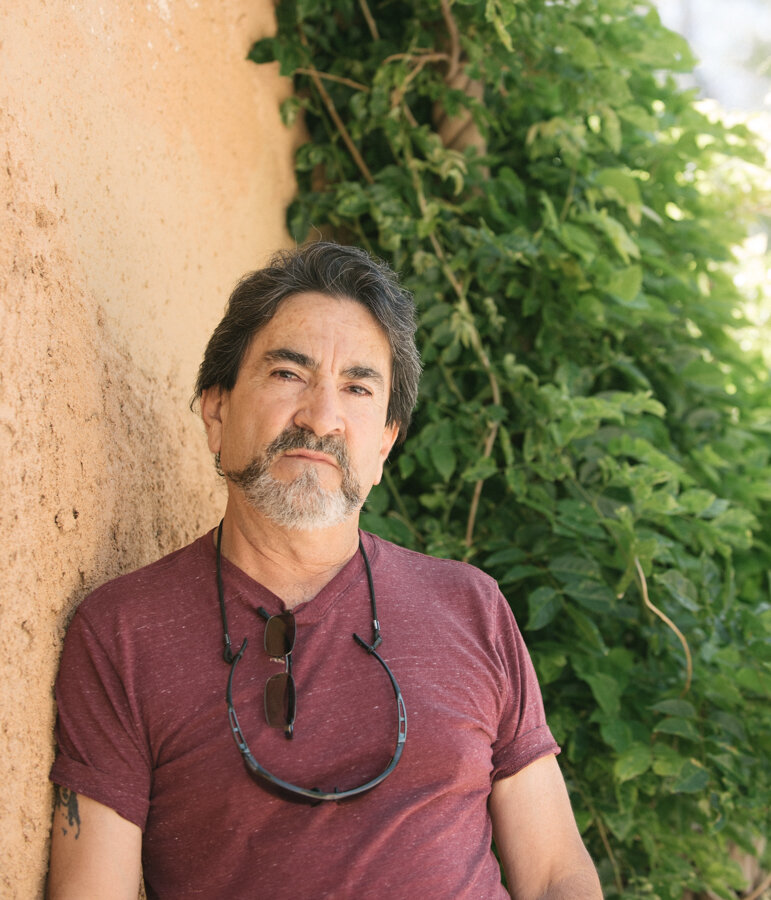

The Robert Garcia that Robert Garcia always saw in the mirror was the Marine who jumped out of helicopters, the guy who built houses, rode a Harley and had plenty of buddies. Now, thanks to the coronavirus, his reflection shows a man alone in a single room in Santa Fe, N.M., out of work, looking outside and wondering what the neighbors are thinking when the food bank delivers his meals.

“People see them coming and I feel this anxiety that they look at me in a different way,” Garcia said. “Like, ‘What’s wrong with this dude that he’s getting food like that?’ ”

Until March, Fran Bednarek, a nurse in Santa Fe, traveled to the homes of people in need and helped them figure out how to keep it together. Now, she has lost all her income, is stuck inside, and depends on a charity’s weekly boxes of frozen dinners.

“I’ve been fiercely independent all my life,” she said. “I don’t ask for help. I keep thinking, ‘Are you sure I can have this?’ I get kind of a guilt feeling of not being able to pay my own way.”

In Santa Fe, the number of people receiving meals from Kitchen Angels, the nonprofit that is helping Garcia and Bednarek, has shot up by 27 percent in the past six weeks, said Jeanette Iskat, the agency’s client services manager.

“I’ve always been self-sufficient and I was taught to take care of myself,” said T’cha-Mi’iko Cosgrove, a 73-year-old artist who was studying at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe when the virus hit, closing the dormitories and dining hall. Now, with no job, no school and no income, he relies on food handouts, with no end in sight.

“I don’t know where I’ll go or what I’ll do,” he said. “But I’m not panicking. Today, I’m just not thinking about it.”